Hook & Introduction

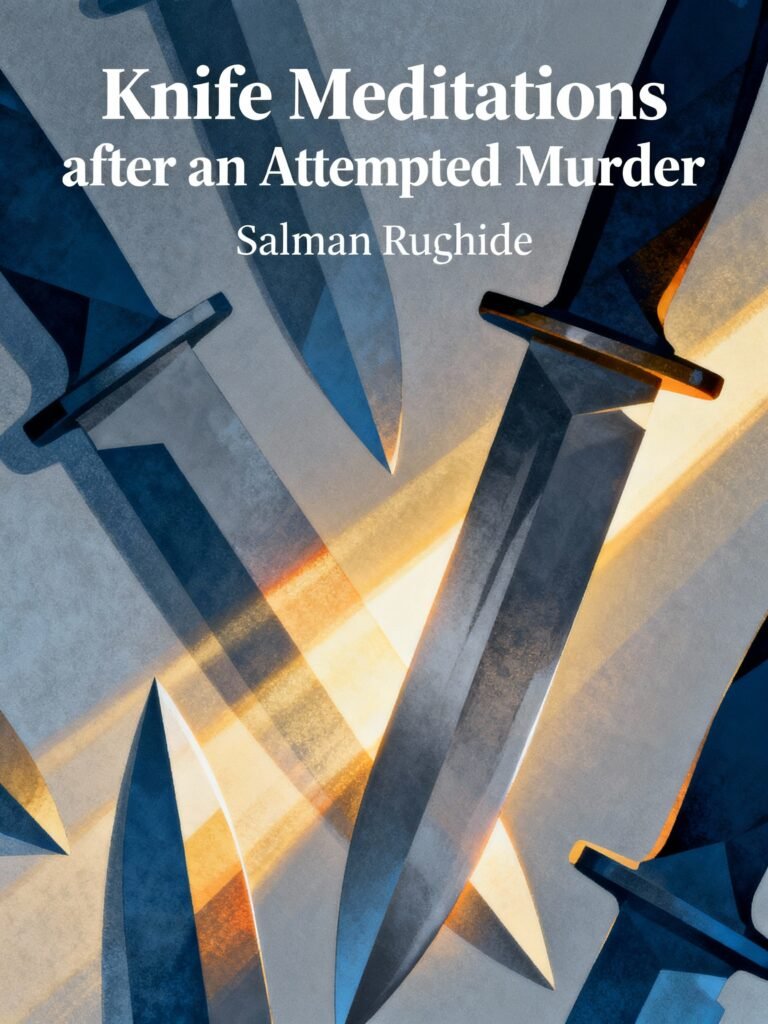

What happens when violence shatters your world, but love picks up the pieces? On a sunny August morning in 2022, Salman Rushdie—the celebrated novelist who has spent decades exploring the human condition through literature—discovered the answer firsthand. At seventy-five years old, standing on a stage at the Chautauqua Institution in upstate New York, he was attacked by a man with a knife, sustaining multiple life-threatening wounds. Yet this is not a story that ends in darkness.

Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder is Rushdie’s haunting, defiant, and ultimately triumphant memoir about the attack that nearly killed him and the extraordinary journey of physical and spiritual recovery that followed. Published in 2024 by Random House, this book combines the philosophical depth of a meditation with the narrative power of lived trauma, crafting something that feels urgent, honest, and utterly unforgettable. For anyone interested in resilience, literature, love, or the human capacity to transform catastrophe into meaning, this is essential reading.

The Anatomy of Violence: When Reality Becomes Incomprehensible

Rushdie opens Knife with a meticulous, almost cinematic account of the attack itself. In just twenty-seven seconds, a stranger with a blade changed everything—leaving the author with a severed optic nerve, multiple stab wounds across his neck, chest, hand, and face, and the philosophical question that would haunt him: why didn’t he fight back?

What makes this recounting extraordinary is Rushdie’s refusal to dramatize. Instead, he examines the psychological fracture that violence creates. When a target of violence finds themselves suddenly in its presence, they experience what he calls “a crisis in their understanding of the real.” The frame in which we understand the world—that a stage is a performance space, that a public event is a safe gathering—shatters. In that shattered moment, rational thought becomes impossible. The mind doesn’t know what “thinking straight” means anymore.

This insight transcends the personal trauma and speaks to something universally true about violence itself: it unmakes reality. It leaves victims disoriented, not just physically but existentially. Rushdie’s refusal to apologize for his frozen response—to resist the shame of inaction—is liberating. It’s a permission structure for anyone who has experienced violence: your paralysis was not weakness; it was the natural human response to the incomprehensible.

The attack itself occupies only a portion of Knife, but it casts a shadow across the entire narrative. What lingers is not the violence, but the aftermath—the rehabilitation, the emotional reckoning, and the slow, uncertain return to a life worth living.

Before the Knife: A Love Story Worth Saving

One of the book’s greatest strengths is how Rushdie contextualizes the attack not as the beginning of his story, but as an interruption of it. To understand the depth of what was at stake on August 12, 2022, we must first understand what he had found just five years earlier.

Rushdie met Eliza (Rachel Eliza Griffiths, the accomplished poet, novelist, and photographer) in 2017 at a literary festival. What unfolds is a tender, witty love story—one told with the same lyrical precision that defines his fiction. After years of romantic disappointment and a self-proclaimed acceptance that the “romantic chapters” of his life were over, Rushdie encountered someone who, quite literally, knocked him through a glass door at a rooftop party. (Yes, you read that correctly. And yes, it’s as charming as it sounds.)

This section of the memoir is crucial because it reframes the central question of the book: not “Can a man survive attempted murder?” but rather “Can a man who has found genuine happiness after decades of struggle maintain that happiness in the aftermath of violence?” The love story between Rushdie and Eliza becomes the emotional spine of the entire narrative. Their wedding, their private life, their conscious decision to remain off social media and untouched by public scrutiny—all of this matters because it gives us something to fear losing when the knife comes.

This is what makes Knife so emotionally potent. The violence isn’t just an attack on a body; it’s an attack on happiness, on love, on the life they had so carefully built together.

Rehabilitation: The Long Walk Back to Self

The second half of Knife documents Rushdie’s physical and psychological recovery. He spends weeks in the hospital, months in rehabilitation, undergoing surgeries to repair the damage to his hand, his face, his eye (which he would lose permanently). But beyond the medical procedures lies the deeper work: learning how to be in his body again, how to move through the world, how to write.

Rushdie explores the concept of “gumption”—drawing from Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance—as the spiritual fuel required to reconnect with quality and purpose after trauma. He reflects on previous moments in his life when he had to “pass through the looking-glass” and rehabilitate himself: leaving his troubled family home, surviving the Khomeini fatwa and decades of police protection, moving from London to New York. The knife attack becomes the fourth such passage, another forced reckoning with identity and selfhood.

What’s remarkable is that Rushdie doesn’t present recovery as linear or complete. He’s honest about the days when despair felt like the appropriate response, when surrendering seemed easier than fighting. He imagines taking “the Philip Roth road out of literature” and walking away from writing altogether. Yet something deeper—some “part of [him]” that whispered “Live. Live.”—persisted.

The role of language and literature in this recovery cannot be overstated. For Rushdie, the knife becomes a metaphor through which to understand his own life. If a wedding knife joins two people, if a kitchen knife enables creation, if Occam’s razor cuts through complexity, then perhaps language—his primary weapon and tool—could be used to reclaim, remake, and ultimately own what had happened to him.

Happiness in a Broken World: The Philosophical Heart of the Memoir

One of Knife‘s most penetrating meditations concerns the ethics of happiness in a world of suffering. Rushdie asks: Is it morally defensible to claim happiness when a pandemic has killed millions, when democracy is under attack, when refugees are fleeing war, when the planet itself is in crisis?

This question haunts him because he knows the answer is complicated. He resists the temptation to present recovery as neat redemption. Instead, he sits with the paradox: that happiness exists in a world that is simultaneously monstrous, that love persists despite violence, that joy and tragedy are not mutually exclusive but rather intertwined.

Drawing on Primo Levi’s observation that while perfect happiness is unattainable, so too is perfect unhappiness, Rushdie finds a philosophical middle ground. He argues that to turn away from happiness—to insist on guilt, on the primacy of suffering—is itself a kind of self-deception. The world’s monstrosity does not nullify the sweetness of the particular. Eliza’s presence, the support of family and friends, the act of writing itself—these things are real, just as real as the violence that tried to unmake them.

This refusal of false penance is quietly radical. Knife argues, without ever stating it directly, that survival and happiness are not indulgences but acts of defiance against those who would destroy us.

Why You Should Read Knife

For survivors and those who love them: This book speaks directly to anyone who has endured violence, trauma, or life-altering loss. Rushdie’s unflinching account of physical and psychological recovery offers not empty platitudes but hard-won wisdom. His refusal to shame himself or others for the human response to trauma is genuinely healing.

For readers of literary nonfiction: Knife combines the narrative drive of a thriller, the philosophical depth of an essay collection, and the intimacy of a personal journal. Rushdie’s prose remains luminous even when describing darkness. The book is structured in two parts—”The Angel of Death” and “The Angel of Life”—and moves with deliberate, meditative pacing. Some chapters are only a few pages, allowing the reader’s mind to settle and process.

For those interested in the writer’s life: This is Rushdie’s most intimate work. He reflects openly on earlier rehabilitation moments in his life—leaving his father’s house, surviving the fatwa and decades of protective custody, beginning anew in America. The book becomes a meditation on what it means to remake oneself multiple times across a single lifetime.

For anyone navigating love after hardship: The central love story between Rushdie and Eliza is portrayed with such tenderness and humor that it becomes a model for how two people with complicated pasts can build something genuine. There’s a quiet celebration here of second chances, of finding love not in youth but in wisdom.

For readers who value honesty: Rushdie doesn’t pretend to have all the answers. He admits doubt, despair, and the temptation to surrender. This vulnerability makes Knife feel like a genuine conversation rather than a performance.

The tone is intimate but never self-pitying, philosophical but never abstract. You can almost feel the weight of recovery, the slow return of agency, the tenderness of being loved despite your brokenness. This is not a book about a man overcome by trauma; it’s a book about a man who insisted on life, who chose to write his own ending.

Call to Action

If this story speaks to your curiosity about resilience, about literature, about the possibility of love in dark times, grab your copy of Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder today on Amazon and discover how Salman Rushdie transformed attempted annihilation into eloquent, life-affirming art. This is the kind of book that stays with you long after the final page.