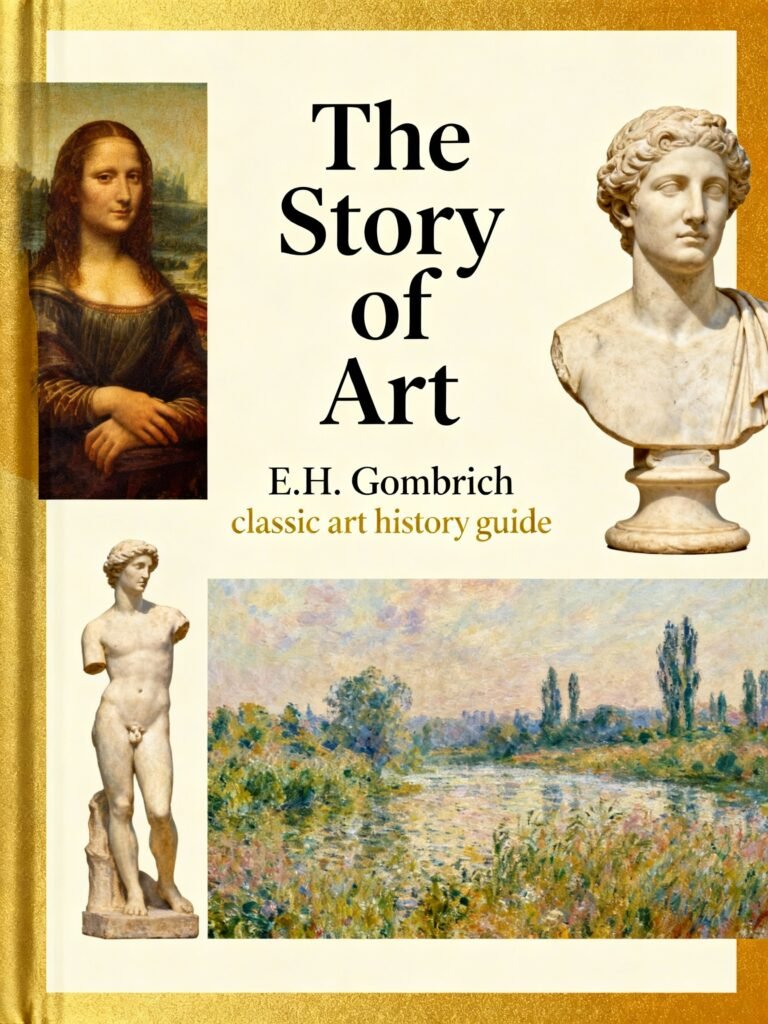

The Story of Art book cover featuring classic art history masterpieces

Hook & Introduction

Have you ever stood before a painting in a museum and wondered why it moved you—yet felt too intimidated by the centuries of art history to understand why? What if someone could explain the entire story of human artistic expression, from prehistoric cave paintings to modern masterpieces, in language so clear and engaging that you’d actually want to keep reading? That’s precisely what E.H. Gombrich accomplished with The Story of Art, a landmark work that has captivated millions of readers since its first publication in 1950.

The Story of Art is far more than a dusty academic tome. It’s a conversational journey through five thousand years of human creativity, guided by one of the 20th century’s most influential art historians. Originally written for teenagers who’d just discovered their passion for art, this book transcends age and expertise level. Whether you’re a seasoned collector, a curious student, or simply someone who wants to understand why a Van Gogh moves you more than a photograph, Gombrich meets you exactly where you are—and takes you somewhere profound.

The book’s genius lies not just in what it teaches, but in how it teaches. Key takeaways from The Story of Art include understanding that art isn’t about progress toward perfection, but rather a constant conversation between artists and their times. Gombrich dismantles the myth that appreciating art requires years of study. Instead, he offers something more valuable: a framework for seeing.

Core Summary: A Page-Turning History of Human Vision

The Story of Art opens with a revolutionary proposition: “There really is no such thing as Art. There are only artists.” This seemingly provocative statement sets the tone for everything that follows. Gombrich isn’t interested in Art with a capital A—that abstract, intimidating concept that makes people feel inadequate in galleries. He’s interested in the real people who picked up brushes, chisels, and pens to solve problems, express ideas, and make sense of their worlds.

The book’s journey spans 27 meticulously researched chapters (now 28 in newer editions), each devoted to a specific era and geographical region. It begins in the caves of prehistoric France and Spain, where our ancestors painted bison and horses onto stone walls not for decoration, but as part of hunting magic—a concept Gombrich brilliantly connects to our modern understanding through relatable examples. He asks you to consider your own reluctance to harm a photograph of someone you love, revealing the “primitive” impulses that still live within all of us.

From there, the narrative moves through ancient Egypt, where art served the afterlife. Gombrich explains the Egyptian convention of showing bodies from multiple angles simultaneously—not because artists couldn’t draw correctly, but because completeness mattered more than realistic perspective. The head in profile, the eye full-face, the shoulders frontal: each element shown from its most characteristic angle to ensure nothing essential was lost. This isn’t primitive; it’s brilliantly logical.

The Greeks transformed everything. Gombrich walks readers through the revolutionary moment when artists began asking not just how to represent reality, but why. This inquiry led to the discovery of proportion, movement, and the subtle play between idealization and observation. The Renaissance, born centuries later in Florence, rediscovered these principles and pushed them further.

But here’s what makes Gombrich’s approach so distinctive: he doesn’t present this as an upward climb toward perfection. Each artistic breakthrough in one direction meant sacrificing something in another. Medieval art sacrificed anatomical accuracy but gained spiritual depth. The Renaissance recovered realistic representation but initially lost the emotional power of Gothic intensity. This is the key insight that separates genuine art history from mere chronology: every generation of artists deliberately broke with tradition, and every break was both gain and loss.

The book explores how art reflected the societies that created it. Caravaggio scandalized Rome by painting Saint Matthew as a working man with dirt under his fingernails—because when Caravaggio tried to imagine how a poor publican would actually struggle with the task of writing scripture, this was the truth he saw. His first version was rejected as disrespectful; society wasn’t ready for that level of honesty. He had to compromise, but Gombrich uses this story to illuminate something vital: artists often see more clearly than the societies they’re born into, and society often resists that clarity.

Moving through the centuries, readers discover how Northern European art developed its own magnificent traditions, how Islamic cultures created astonishing geometric beauty without representing the human form, how Chinese landscape painting achieved profound subtlety through restraint. The Renaissance spread north, but artists like Albrecht Dürer didn’t merely copy Italian innovations—they synthesized them with their own traditions, creating something new.

By the time Gombrich reaches the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, he’s established readers firmly in their capacity to understand radical experimentation. When Picasso distorts a cockerel’s features to capture its aggression and stupidity, or when impressionists abandon browns and blacks for pure color, readers grasp not chaos but intentional choice. Artists aren’t bungling when they deviate from realism; they’re communicating something that literal representation cannot.

Why You Should Read It: The Perfect Entry Point for Art Lovers

The Story of Art is the rare book that serves multiple audiences simultaneously. For art students and enthusiasts, it provides the foundational framework that makes specialized study vastly more rewarding. You’ll finally understand why artists made the choices they did, which transforms passive viewing into active dialogue with history. For curious generalists intimidated by art’s apparent complexity, Gombrich demystifies without dumbing down. He refuses to use pretentious jargon, yet never talks down to his reader.

What makes this book uniquely powerful is Gombrich’s conviction that anyone can develop taste in art. He argues persuasively that this isn’t about innate sensitivity but about patience and willingness to look carefully. Just as someone unaccustomed to tea might initially find all blends indistinguishable, your palate for art develops through attention and exposure. Once developed, that refinement dramatically amplifies your pleasure.

The book’s tone—balanced between intimate conversation and scholarly authority—feels like being guided through a gallery by someone who loves the subject but refuses to be pompous about it. Gombrich shares his genuine uncertainties, admits gaps in knowledge, and laughs at his own quirks. He’s witty without being clever, passionate without being sentimental. You can almost feel his conviction that art matters, not as status marker but as proof that humans create meaning.

One particularly remarkable feature: the book actively teaches you to see beyond surface beauty. Gombrich confronts the bias toward “prettiness,” using examples like Dürer’s portrait of his elderly mother versus a more flattering work. The aged face, with its lines of suffering and wisdom, contains greater beauty than mere charm. This reframing—that true artistic power often lies in honesty rather than decoration—is genuinely transformative.

Over eight million copies have been sold worldwide, translated into more than 30 languages, and it remains continuously in print since 1950. The New York Times has called Gombrich “probably the world’s best-known art historian,” and Time magazine included The Story of Art on its list of world’s top 100 non-fiction books. Readers consistently report that this single book changed how they experience not just museums, but the visual world itself.

For anyone planning museum visits, traveling to Europe’s great galleries, or simply curious about how humans have seen and represented their world across millennia, this book functions as both preparation and lasting reference. The generous illustrations—more than half the book’s pages feature color photographs—mean you’re not just reading about art history; you’re seeing it unfold.

The book also teaches an often-overlooked truth: appreciation isn’t passive admiration but active engagement. Gombrich insists that misunderstanding often stems not from artworks being difficult, but from viewers approaching them with preconceived notions. A medieval crucifix speaks differently than a Baroque one not because one is “better,” but because each artist was solving a different problem with different tools. Once you understand the artist’s probable intentions, the work opens up.

Conclusion: Your Invitation to a Timeless Conversation

If this story speaks to your curiosity—if you’ve ever wondered why certain artworks haunt you, or wanted someone intelligent and warm to explain the actual evolution of human visual culture—there’s no better companion than The Story of Art. Whether you read it cover-to-cover or dip in and out by era, Gombrich meets you with patience, humor, and genuine reverence for the subject. He doesn’t demand that you become an art expert; he simply invites you into a conversation that’s been unfolding for five thousand years, and offers you the tools to participate meaningfully.

Grab your copy of The Story of Art today on Amazon and join millions of readers who’ve discovered that understanding art history isn’t about memorizing names and dates—it’s about learning to see the world through the eyes of every human who ever tried to capture truth, beauty, or meaning on a surface. This book will change how you move through galleries, how you respond to images, and ultimately, how you understand the human impulse to create.